Detailing the puppyhood of an overzealous Labrador.

By George W. Calef

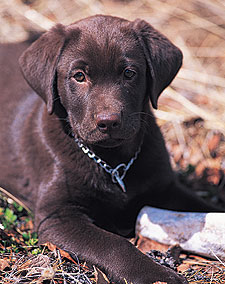

The Prodigal Daughter" as a puppy. |

She arrived on the requisite 49th day, as per the gospel according to Richard Wolters. And she did not come quietly. I could hear her barking madly half a mile away as the baggage cart rattled metallically across the bleak asphalt tundra of the Whitehorse airport.

In the cargo office when I opened her traveling crate, she marched boldly outside, her tail held high and wagging confidently as she snuffled around, nose to the ground, in the rank weeds and litter that always seem to arise spontaneously around industrial sites. While she stretched her legs and had her first pee in the Yukon, I read the note taped to the cage by Mrs. O'Grady, her breeder: "Here's Heidi. Just remember, she's only seven weeks old and she's a good girl."

My previous dog had been a fine male black Lab and I wanted the new pup to be totally different so she wouldn't remind me of Tarka. I had been researching and writing to kennels for months, searching for a female chocolate Lab, and now, eight months later, I was the hopeful owner of Heidi. And while she was, indeed, "only seven weeks old," I would quickly discover she was not "a good girl."

She fought and fussed and barked in her kennel on the truck seat all the way home, and in the canoe crossing the river. When I finally set Heidi down on the floor of my cabin she planted her feet, looked me in the eye and barked even louder, as if to say, "Who are you? What is this place? Why did you bring me here? And what are your intentions?"

Well, my first intentions were to feed her. And when she smelled the food she gave me a hint of the most prominent of her good traits, her athleticism. At seven weeks she could jump higher than the kitchen counter, and she did it over and over, seeming to levitate each time she touched the floor, as if she had springs in her feet.

And she barked even louder, if that were possible. Each time she reached the peak of her trajectory she exploded in my ear.

That was the first demonstration of just one of her bad characteristics--always expressing her hysteria with the loudest bark of any dog I've ever heard. Brodie, my wife, maintains to this day that her formerly extraordinary hearing was ruined in the first six months of living with Heidi.

Pheasant hunting in the sagebrush country in eastern Alberta. |

She barked at everything--other dogs, cars, bicyclists, and even road signs on the highway. She barked when it was time to go for a walk; she barked when I stopped walking. She even barked at me; if I walked into the woodshed and came out a few seconds later it was as if I had gone in and the boogie man had emerged.

Over the first few weeks she presented such a peculiar combination of good traits and bad, strengths and weaknesses, that she almost drove me crazy, and to the verge of selling her down the river.

On the good side, she came running every time I called. In my experience "come" is the hardest command to perfect, but she would always respond, even when there was a distraction. Conversely, she absolutely would not stay.

I tried endless repetition. I tried yelling at her. I tried bribery with food. I even, I hate to confess, thrashed her, since she clearly knew exactly what I wanted yet would not do it.

But nothing would allow me to walk more than 10 feet away from her before she got up and followed.

The author's wife, Brodie, and Heidi with Alberta pheasants. |

Having a dog that won't stay put makes it awfully hard to sneak up on ponds to jump shoot ducks, or to decoy approaching waterfowl. It took me a long time to realize that she was simply bonded to me so completely that nothing--NOTHING--was ever going to separate us. Yet, strange to say, as much as she wanted to be with me, she had no interest in praise or being petted.

(Years later, at dinner one night, I was describing the peculiarities of Heidi's personality to one of my hunting partners and his wife, a specialist in childhood development problems. After she had listened for a while she pronounced simply, "Heidi's autistic.")

Her strength and determination were not in doubt. One day we tried to go to town without Heidi, and left her chained to her doghouse inside a four-foot-tall wire pen. We were halfway across the river when Brodie suddenly saw Heidi swimming frantically after us.

"Look at how fast that little monster can swim!" she said.

"Yes" I replied, with a slight reservation, "but she doesn't seem quite as fast as normal."

When she came panting up to us after having been swept several hundred yards downstream the reason became clear. This barely three-month old pup had yanked the huge staple out of the wood, climbed the fence, and swum the swift river dragging 20 feet of chain.

Neither was her intelligence lacking. It usually took only one or two lessons to learn what was expected of her. Unfortunately, her stubbornness exceeded her intelligence and athleticism combined.

Worst of all, she didn't particularly want to retrieve. When she did, she just wanted to run around with the dummy, of course, and play "keep away." Wolters' trick of running away, clapping your hands while calling "come," then snatching the dummy away as the dog comes alongside and immediately praising her worked--precisely once. She was much too smart to fall for it again, and too agile besides.

When she did bring a dummy to me she would drop it. I'd put it back in her mouth, hold my hand under her chin and encouragingly say "hold." She'd look me in the eye and spit it out. After several repetitions I'd give her a whack and shout at her, and she would finally, reluctantly hold it. Then I'd hold out my hand and say a friendly "Give." She would look me in the eye and clamp down on it.

Then one day as I sat writing at the kitchen table, a solitary san

dpiper (Tringa solitaria) the only solitary sandpiper, in fact, that we have ever seen at our cabin, flying as fast as a solitary sandpiper can possibly fly, smacked into the window. As I examined the dead shorebird, an idea stuck me as suddenly as the sandpiper had struck the glass.

I called Heidi. I jumped around, talking excitedly, teasing her with the warm bird, then threw it and sent her. She raced over, but at the bird she seemed unsure of the unfamiliar smell and texture. She brought it back gingerly, holding one wing in her teeth, her lips curled delicately back.

My heart sank. Would this pup never be a retriever? But I threw it once more and her response was more enthusiastic. I threw it again and again, and gradually the smell and feel of the real thing started triggering latent instincts.

She began sprinting out, grabbing the now bedraggled bird and running back so I would throw it again. A switch had been flipped; from that day on retrieving was fun.

The author and Heidi with a mixed bag in the Peace River country. |

Two months later Brodie and I were paddling down the Big Salmon River during moose season. As we rounded a bend a little band of green-wing teal scattered off a mudbar. My knockabout double gun is always leaning against the thwart for just such an exigency, and I instinctively grabbed it and made the shot.

As luck would have it, not one but three tasty little teal hit the water, one stone dead, one low-sneaking toward shore, and a third flapping away down the current. Heidi leaped up, lurched across the tarped-down load in the freighter, and teetered indecisively on the gunwale. Then she launched herself into the Big Salmon and paddled powerfully over to the dead teal.

She swam back with it and held on while Brodie grabbed her by the scruff of the neck and hauled her over the side, along with several gallons of water. Heidi dropped the duck, and immediately dove overboard again in pursuit of the bird swimming downstream.

She made her second retrieve, then we paddled into shore and found the third teal hiding in a beaver hole. "Just maybe there's some promise here after all," I allowed myself to hope.

Mid-October found us beside a big pothole lake in central Alberta. I had shot a couple of ducks and Heidi made routine retrieves in the open water. Then a big mallard drake came out of the sunrise and cruised by, flying slow and straight. I rose from the willows, swung smoothly, fired, and watched in disbelief as the duck continued unruffled across the lake.

Heidi of course broke shot and was prancing around on the muddy shore looking for something to retrieve while the drake continued on in an absolutely straight line. I watched the bird's flight until just before it vanished in the mist, when I saw it bank over the stubble field and turn back toward the lake.

We shot a couple more birds, then the morning flight slowed. I said to Heidi, "Let's go across and see if we can find that duck." We had to walk almost a mile around the shore to reach the vicinity where I'd last seen the mallard.

The slough there displayed as forbidding a phalanx of vicious plants as possible: wild roses, thistles, raspberry canes the size of the giant's beanstalk, and everywhere, aspens and willows cut down by beaver, jumbled like jackstraws in the waist high weeds.

I sat Heidi down in the stubble a hundred yards downwind of the tangle. Her tail was wagging furiously. I gave her a vague line (I really had no idea where that bird was) and sent her off. The little brown rocket disappeared over the rise.

She was gone for several minutes. I had already started whistling her back, lacking the conviction that she was going to accomplish anything, or even that the duck was actually down, when I saw her trotting into the field with the drake in her mouth. I dropped to one knee and put my arm around her neck as she came up beside me and laid the heavy grey body in my hand.

The prodigal daughter had come home.

Epilogue

Heidi has never learned to stay, or to enjoy affection. She still fidgets and moans while we wait for ducks and geese, and breaks shot unless threatened with the electronic collar, something I do only when absolutely necessary.

When she was 6½, we discovered her true calling: hunting pheasants. Upland work provides the much-needed outlet for her boundless energy.

She has flushed and retrieved in places as different as sagebrush coulees in stifling heat to ice choked rivers with a below-zero chill factor, and she has brought to hand everything from tiny snipe to 15-pound geese.

This fall we hope to make a big trip to add a few more species to her life list. I expect all will go well, just as long as I don't try to show her how much I love her.