A crisis every dog owner has to face.

By Charles F. Waterman

Bird dogs get lost, generally get found again, and it's strange the problem isn't worse than it is. We take a dog into strange, wild country filled with unusual scents and sights, turn him loose and tell him to keep moving.

There are big-going, hard-driving speedsters who seem never to have been misplaced for a moment and there are otherwise highly intelligent veterans who have spent much of their lives being sought by frantic, furious handlers who wish they had taken up some other hobby. There is no other dog problem that demands more study and none that is more vague in solution but it pays to figure how the dog gets lost in the first place and sometimes it can be prevented. It shouldn't get boring because no two cases seem to be the same.

It is generally the wider-ranging dogs that aren't ready to load up when the day's over--a simple matter of being under less control most of the time. Remember too, that a good share of the misplaced ones are runaways who were surprised they didn't know the way back to their boxes when the sun sank.

I've had more problems with deer chasers than anything else. Trailing wild animals, we must remember, is an instinct stashed somewhere in almost every dog's makeup. The deer keeps going until the return trail is a long and tough one. I have never felt a deer, whitetail or muley, was as playful as a pronghorn. A pronghorn, completely confident in his ability to run away any time he really wants to, will stay just far enough ahead of a dog to keep him coming and when he finally takes off the dog is exhausted. The good part about the antelope chase, however, is that the dog is probably running by sight and will get tired pretty quickly, near enough the starting point that he is likely to limp back to his boss.

Not always.

Back roads through brushy country can be an attraction for dogs that have been hunting hard--and sometimes they follow them until they're seriously misplaced. |

How do you break a dog of deer chasing? I have done a fairly good job by using an electric collar and working the culprit to where I was sure he'd get a closeup view of a deer--and as the deer took off with the dog following, I'd use fairly strong electricity.

Was the cure permanent? I'm afraid it wasn't a forever cure in at least one case. After a couple of weeks the dog resumed some deer trailing but he did it sneakily and never sight-chased a deer. He'd stick to a trail for a little while and then sneak back to where he belonged. It was an improvement if not a complete cure. With another dog the electric collar seemed to do the job permanently but he never had been as much of an enthusiast as the first specimen.

Since the "continental breeds" come from stock that is sometimes trained to hunt fur as well as feathers, it's logical to assume they'd be more likely to follow something besides gamebirds. That may be true but most of them work closer than English pointers and setters and are therefore easier to control with deer and the like. This whole business is full of exceptions though.

When a deer chaser doesn't come in on time he may not actually be badly lost but his backtrail may simply be so tangled it takes time. I lost a strange pair--a steady old Brittany and a rather goofy English setter--at the same time. I assumed the setter had taken a deer trail and the Brittany had followed him. Anyway, I camped on the spot I'd lost them in mid-afternoon and they came in around two the next morning. With the typical dog owner's thinking, I guessed the young setter had been lost and the old Brittany had hunted him down, but who knows?

I had a Brittany who had appeared mildly interested in deer. I lost him in deer country late one afternoon and gave up shortly after dark after shooting up half a box of shells, blowing a whistle until my lungs hurt and traveling a lot of miles over sand roads. It rained very hard that night and we guessed that one had no chance of backtrailing himself but we set out a dog box with food and one of my shirts and he was there at dawn. He had pretty well come apart and crawled to the truck instead of walking. He was cured for at least a year or two.

It's quite possible that some dogs who "refuse to hunt" or simply won't cover enough territory are simply afraid of getting lost and occasionally there's a hopeless case of this kind.

And I have known several dogs who insisted upon hunting "outside" any dog they were paired with, no matter how far that took them. They get too far out for practical hunting and can get misplaced in short order.

The true runaway can be impossible--one that deliberately tries to escape control and often never comes back. I was chasing quail with a veteran dog user who claimed he had a setter bitch that continually sought a new home. Sure enough. On the first day I went with that combination the setter didn't seem ready to be picked up at quitting time and despite our calls and whistles her bell sounded fainter and fainter until we couldn't hear it at all. "She's run away again," her owner announced sadly.

We were in a much-hunted area where lost dogs were no novelty and a week later the folks who had picked up the setter charged quite a ransom. Her owner had never abused her. Such a deliberate and regular runaway is bad news and not likely to change. I had to give up on an intermittent runaway who felt anybody's car or truck was a place to rest late in the day. The last day I hunted him he chose to load up in somebody else's rig when it was parked within 50 feet of mine and he had to be dragged out. Most of the time he thought I was wonderful. It was embarrassing to realize I had put up for months with a pretty dog that was off his rocker.

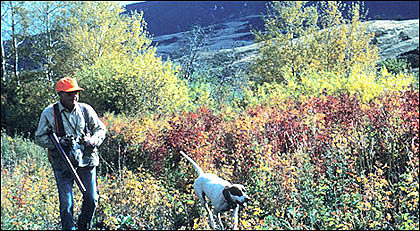

Ruffed grouse country in the mountains can be confusing to hard-working dogs, even after long experience, if they run a little too wide. |

On some days in some places the scenting conditions evidently make it impossible for a dog to backtrail himself, even for short distances. I ran into that with another hunter when we were chasing ruffed grouse in reasonably rugged but fairly familiar hill country. We were using two dogs and both of them kept getting completely lost at fairly short range. It was a chilly day with snow on the ground, a patchwork of brushy draws, scattered pines and some aspen patches. We had two veteran male Brittanys, both of which ranged moderately and both of which had hunted the area before.

One dog got lost and (unusual for him) started

barking. I went toward the sound and got him to come to the whistle. He acted as if he'd been lost for a month and I had saved his life.

Twenty minutes later the other dog got lost and the procedure was the same. Then Number One was misplaced for the second time and my buddy went to him. By that time we'd had enough of stumbling after them so we hunted the rest of the day along a creek where we could watch them constantly.

A little reticent about reporting such a goofy program, I checked with another acquaintance who had hunted that day and he said it hadn't been much of a trip. He said his dogs "couldn't smell anything." That made me feel a little better, but not much. I have bored my friends with this story for years but it's worth remembering that there are some days when dogs bear extra watching if they range widely. A brief loss is an indication.

It's seldom that a dog plans to wander the second you turn him loose. There's generally something special to get him headed too far. I had a pointer who became hard to handle if she found no game after considerable hunting. She'd go farther and farther, and whether you could say she'd get really lost or not I don't know. I do know that after performing perfectly without result for a couple of hours she'd simply quit "hunting to the gun" and start hunting for herself. Maybe she always knew the way back but sometimes it was a long trip and once she was brought in at dusk by someone who had picked her up (beeper and all) and hauled her to where I was looking for her, shooting in the air, blowing a whistle and talking vehemently to myself.

I guess that's self-hunting all right, carried to extreme several times. I think she could have found her way back at any time and once she decided to come in she back-trailed pretty rapidly. On a slow day in mountain country she disappeared before noon, having found no birds. Near sundown, we took the truck to the spot where she'd first been released and waited without much hope. At dusk we sighted her coming at top speed--a white speck near the top of a high ridge, smoking back along the route she'd taken that morning. She never trailed deer as far as I know. I think that when hunting was slow she sometimes simply went into high gear and hunted for herself.

Some kinds of terrain encourage wandering. I've had a dog hunt carefully at moderate range and then come to a back-country road or railway and take off for long distances. After going through brush, grass and weeds, he suddenly finds this opportunity to run fast and still catch the roadside scents and he goes farther than he intended to. Good way to get lost if he then turns off a mile or two down the line. I had a road runner once and I took special care when he came to a good takeoff spot.

Whistle and beeper locations can be deceptive, especially in mountain country. I lost two dogs on a high, timbered bridge and from far below them I could actually hear their beepers but got no results from my whistle. It seemed impossible that they couldn't hear me but as evening came on I decided to climb up there. I was already tired and clawing over that brush and boulders was not a happy prospect, but I finally did it, getting up there just before dark. I met one dog in an open space and it was pretty obvious he didn't know where he was. I then sighted the other one on a distant slope and he could then hear my whistle and came to me. They both acted a little scared. I have no idea why they couldn't backtrail themselves down to where they started up. Both were veterans although they had never hunted in that exact spot before.

Although strays often find their way back under very tough conditions, lost dogs sometimes change quickly into unreasonable fugitives who actually try to avoid anyone trying to rescue them. I got a strange jolt of that on one of the very first times I followed bird dogs.

Dogs that have been temporarily lost are likely to be a little confused when they are found and special treatment can be called for. It's helpful for the handler to be a canine mind reader. This dog is a little scared. |

Two of us were using two veteran dogs and a pup on one of his first trips in big, open country. We had made a considerable circle and were returning to our truck, which was parked in plain sight with no nearby trees. The pup went over a hill, out of sight, and apparently thought he had been abandoned, but he somehow beat us to the truck. We were a long way from the rig when I first saw it, and I made out the pup, just a speck, moving around it. But while I watched the pup took off at a run, following the route we had taken when we left the truck hours earlier.

Now I assume he would have eventually trailed us through the entire hunt and ended up at the truck again, but who knows? I hurried to cut him off and one of the older dogs ran and intercepted him--a squirming, wriggling bundle of terror who was afraid of me and the older dog too for several minutes. The moral to this story is that dogs lost for the first time are scarily unpredictable. Okay, okay. We made a mistake. He was too young, but older dogs can become strangers when lost.

When he's gone, it's natural to think of the things that could happen to him on his own. Some dogs will hop into anybody's car and some become spooked and won't even get into their owner's. I had one who had been worked with horses and was likely to bed down in any strange horse trailer.

Of course there are things that can kill lost dogs. Coyotes will do it sometimes, especially when the victim is young and uncertain. Sheep ranchers who have had losses are likely to use scope-sighted rifles. In the South, alligators are deadly.

But most of the things that can kill dogs do it after the dog makes the attack and most lost dogs are not aggressive. There are no fast rules.

Great numbers of hounds are permanently lost by deer hunters in the South and I've stirred up numerous stories on that subject, some of the problems applying to pointing dogs as well. One of the most chilling cases regarded loss of an incredible number of deer hounds in a big southern forest during extra high water. Many of the bodies were found--dogs that had electronic locating devices. They had simply trailed too far into deep water and drowned.