The "here" command should be one of the first lessons pup learns...and learns, and learns.

By Dave Carty

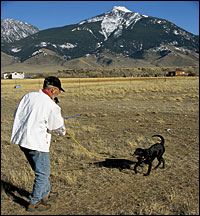

Joe Skaggs keeps the light lead on Raven, a four-month-old Lab, whenever she's in the house. The training is exactly the same for pointers. |

Years ago, I ran across a cartoon that perfectly depicted a bird dog's selective hearing. A man is scolding his dog, which sits watching him, wanly thumping its tail. The first caption contains the man's actual words, the second what the dog chooses to hear: Gypsy! blah, blah, blah, blah, Gypsy! blah, blah, blah, blah. I've remembered it all these years because it captures so precisely the personality of every dog I've ever owned. I'll bet I'm not alone.

Let's forget the frills for a moment--the commands "sit" and "heel," hand signals, forced retrieves and all the other niceties that make a good dog a pleasure to live with and hunt over. The huge majority of pointing dogs I see in the field (as opposed to those I've watched in my limited experience with hunt tests and trials), would be vastly improved if they obeyed — really obeyed — just two basic commands: "whoa" and "here." Trying to write about two things at once makes my poor head all mushy, so "whoa" will remain grist for a future column. Today, I'll talk about "here."

There seems to be a need in this country to accomplish any task, no matter how difficult, with the least effort and in the shortest possible time. But it doesn't work that way with bird dogs, certainly not with mine. I have no doubt that the pros, many of whom train more dogs in a week than I'll train in my lifetime, have methods that will bring a dog along more quickly than the ongoing process I use, and with that caveat I'd shamelessly like to plug the other columnists in this magazine as among those you should read for similar thoughts on this subject. I do. But there are so many variables among dogs and so many different situations they run into in the field, that it's probably safe to assume that "here" is a command you'll never stop reinforcing.

That's right, never. That means you can't teach your dog to come and then rest on your laurels, smug in the belief that he'll perform the command flawlessly forever after. Life should be so easy.

There's nothing complicated about the "here" command; you whistle and the dog comes in. But a command performed in the distraction-free vacuum of your backyard doesn't mean squat when your dog is nipping at the heels of a running deer or racing out of sight under the peculiarly canine impression that if he just runs hard enough or long enough he'll catch the bird.

I was inaugurated into the realities of dog training early on when one of my first dogs, a springer, developed a hankering for aircraft. We'd be hunting or training someplace, my anxious eyes scanning the heavens, when, to my horror, a plane would buzz over and off he'd go. I didn't have an e-collar in those days--no one else did, either, back then--so when my screams and whistles had zero effect, I was resigned to chasing him down on foot.

In retrospect, I should be grateful for the lesson. It took Poke only a year or so for the command to sink in, but to grasp what he was teaching me took decades. And that is this: If I wanted my dogs to come when called, I had to be ready to back up my words with immediate action.

The two pointers I now own, Powder, a Brittany, and Scarlet, a setter, come reliably maybe 95 percent of the time in the field and 85 percent of the time at home. That's not perfect by a long shot, but it's a far cry from what I used to settle for. That they're not both at 99 percent I blame entirely on my own laziness.

Having learned the hard way that I need to call my dogs once, and once only, before lowering the boom, I still sometimes let things slide if, for no good reason, I'm just not in the mood to enforce a direct order. My dogs, of course, know exactly how long they can ignore me and invariably do just that before responding. Consequently, they're usually less responsive at home than in the field, where the power steering I strap to their precious little necks allows immediate corrections. Of course, they know that, too.

Ian Munn with Rabbit, the author's last setter. Rabbit was well accustomed to a check cord. |

E-collars aren't a panacea by any means. It might feel good, really good, to slap a brand-new collar on your dog and light him up the next time he ignores your whistle, especially since it usually works. But save your urge for instant retribution for bad books and cops & robbers TV shows. This is going to sound strange to my friends, who know how hot-tempered I can be, but keeping your thumb off the button until you've figured out the ins and outs of electric collars will pay big dividends in the long run. I mean, really try. E-collars are great tools, but only if used judiciously.

Teaching "here" is one of the first things your new puppy should learn. Consequently, I start home-schooling when they're just a few weeks of age. My method doesn't differ from anyone else's: I call the puppy and then praise it when it runs to me. A half-dozen times at one sitting is plenty for a youngster.

Joe Skaggs, a friend of mine who trains and trials Labs, has a different wrinkle. He attaches a light, 12-foot lead to the pup's collar and leaves it there. Permanently. That way, he can enforce compliance instantly whenever he gives the "here" command, and he never gives his pups the command unless he's already got the cord in hand. Joe says his young dogs get used to dragging their cords around, but in any event cords are cheap, and if the pup chews one up, it's easy to tie on another. I think it's a great idea and I plan to try it on my next puppy.

My training progresses from reeling in the dog on a check cord to doing the same in the yard, then in the field. I teach the dog to come on a voice command first, then overlay that command with a whistle, and then use the whistle alone. Eventually, I transition to a collar. The specifics of how I go about doing that vary from one dog to the next, but they're really not that important. Where we invariably fail--you, me, and your sister Kate--is assuming, despite evidence we could plainly see where we not so willfully determined to block it out, that our dog has somehow put his training behind him and no longer needs work.

You can teach a motivated dog to do almost anything. In my not particularly unbiased opinion, that's one of the fallacies of the so-called "positive" approach to dog training: if your dog becomes motivated by something other than obeying your command, your training g

oes out the window.

But often, it is precisely when your dog's motivations are elsewhere that obeying the "here" command is so important: at the end of the day; when the hunt is over; when he's downwind of a porcupine or skunk; when he's about to dash across a busy highway. It is our dogs' single-minded devotion to instinct that makes them so inspiring in the field, but it is also their biggest and most glaring Achilles heel.

Somehow, you have to get through to them. And you have to get through to them over and over again.

At home and in the training field, a dog should be trained with controlled distractions. One example: wait until the little scoundrel chases a pigeon you've planted, and when he does, call him back, then immediately reel him in with the check cord. Or, if you've already transitioned to a collar, give him an appropriately timed stimulus. (Note: I really do mean "stimulus" and not "shock." It is critical when using collars to learn the difference. Punishment via the collar comes later, and only when merited by the dog's willful disobedience to a command you're certain he understands.)

This kind of training is a must, and my dogs have been through weeks and weeks of it. But virtually no contrived training situation, no matter how realistic, holds the allure of real birds on a real hunting trip. The dogs know--and will exploit--the difference. For instance, when my setter is rooting like a barnyard hog through the compost pile behind the house, she knows I'll usually call her twice before I stomp out and get her. Like most bird dogs, she's plenty quick on the uptake when she's doing something she enjoys. And why shouldn't she be? She's doing exactly what I've trained her to do, however unwillingly. I've shown her repeatedly that I'm more lax about enforcing commands at home than in the field, and she reacts accordingly.

And so it goes in the great outdoors. If you don't promptly enforce the "here" command when you're hunting, your dog will learn, with something like warp-speed comprehension, that he can ignore you, even if he obeys flawlessly at home. Trust me on this. It will take him less time to learn this, in fact, than it will take him to learn the location of his food bowl or the whereabouts of the neighbor's cat.

The late Datus Proper whistling for Huck, his German shorthair. Give the command "here" once, then enforce it--even if you have to chase down your dog. |

Which, of course, is the crux of the problem. Few of us, and that formerly included me, want to spend our precious hunting time training our dogs. But you can't have it both ways; you can't effectively train and hunt at the same time. Last year, I solved the problem once and for all by relinquishing my gun for the first month of the season, and then periodically afterwards, whenever I felt one or the other of my dogs needed an update on her manners. It worked. Since I wasn't carrying a gun, I was more than happy to let my friends shoot while I concentrated on my dogs, who learned, finally, that I really did mean business when I whistled them in. Funny thing was, I didn't miss the shooting all that much, probably for two reasons: First, I hunt a lot. And second, the more I hunt, the less I shoot and the more I value good dog work.

One caution, though: Don't over-handle your dog. On a two- or three-hour hunt, I'll use the "here" command (or whistle) three, maybe four times at most, making certain each time that my dog is in sight and within range of my ability to enforce the command with a check cord or collar. For the training to really sink in, your dog has to be completely absorbed in what he's doing. If you hack on him too much, you'll draw him in, where he may become anxious and stop hunting. This is an ongoing problem with my Brittany. One or two enforced commands per trip are plenty for her.

Remember, you're conditioning your dog to come even if he's--and he almost always will be--far more interested in doing something else.

I've heard rumors of perfect dogs but I've yet to see one. No matter how much you train, sooner or later your dog will run into something, or run after something, that he just can't resist, and all your whistling won't faze him. Stick with the program. If your dog will return reliably 95 percent of the time on a single command, you'll be way ahead of the competition and you'll impress the stuffing out of your friends. Even mine sometimes remark at how well my dogs "listen." If only they knew.