Where It Came From And Why It's Useful.

By James B. Spencer

The first part of the blind retrieve is "lining," that is, sending the dog toward the downed bird. Here, the author lines a dog in a bare-ground drill. |

What Is It?

A working definition: A blind retrieve is a retrieve in which the handler directs his dog, by means of voice, whistle, and arm signals, to a downed bird that the dog didn't mark.

After you've watched a few handlers in action, you'll probably feel that the definition should include something about accompanying body-English, some conscious, some not, some helpful to the dog, some not. For now, let's keep it simple.

To direct his dog to an unmarked fall, the handler must first send him in the right direction, which necessitates said handler knowing about where the bird fell. He normally sends the dog from the heel position, sitting beside him, after "aiming" him along a line toward the bird. Not surprisingly, therefore, retrieverites call this initial sending of the dog "lining." If the dog carries that initial line all the way to the bird, without further assistance from the handler, he is said to have "lined the blind," which is a big plus in field trials and hunting tests as well as very satisfying in hunting situations.

Normally, however, the dog doesn't carry his initial line all the way to the bird. Various hazards (terrain, cover, wind and so forth) will induce him to veer off somewhere along the way. When this happens, the handler must stop and redirect his dog. Most retrieverites train their dogs to stop when they hear a single, sharp whistle blast (Tweeet), called the "Sit-whistle." In addition to stopping, the dog should turn to face the handler, sit down, and look at the handler, so he can redirect the dog with an appropriate "cast."

In long-gone days, handlers got by nicely with just four basic casts: Over (straight left or right); Back (straight back); and Come-in (straight toward the handler). For each of these, the handler gave an arm signal plus a voice or whistle command. With those four basic casts, you can still put your pooch onto any bird you might shoot. But over the years field trialers, to gain a competitive advantage here and there, have added so many variations to these four basic casts that they sometimes perform like ballet dancers at the line.

As you can see, the blind retrieve has three parts: lining, in which you send your dog from your side toward the downed bird; stopping, in which you stop your straying dog at a distance; and casting, in which you redirect him. Taken together, these three parts are called "handling." When lining, stopping, and casting your dog, you are said to "handle" him to a blind retrieve (or missed mark). Of course, in a more general sense, the word "handle" also means everything you do while working your dog. Retriever-speak can be confusing for beginners.

One final and extremely important point about the blind retrieve: Unlike marking, it is not natural. No dog of any breed has any hereditary inclination to line, stop, and cast. If you want your retriever to do blind retrieves, you must drill each of these three parts into your dog, first separately and then in combination.

The second part of the blind retrieve is "stopping," that is, stopping the dog in order to redirect him when he drifts off-line. |

Where Did It Come From?

Shortly after WWI, Dave Elliot, a young professional retriever trainer in Scotland, took a day off and went to watch a stock dog trial. There he saw one handler after another, with a simple arm-sweep, send his dog from his side all the way to the far side of a distant flock of sheep. Then, the handler stopped his dog and directed him this way and that with arm signals and whistle commands, so the dog would herd the sheep to the designated destination. Dave was impressed, but more importantly he was greatly enlightened.

He was reasonably successful in British field trials, but his competitive nature wanted much more success. In those trials, the judges had several handler/dog teams on the line at the same time, while distant "beaters" flushed birds toward them, and nearby "guns" shot the birds. Typically, birds were falling here, there, and everywhere. The judges would decide which dog should retrieve which bird.

Often, they asked a dog to retrieve a bird not seen by said dog. If that dog failed to collect the meat, he was dropped and another dog was given the chance to retrieve it. If that second dog found the bird, that handler was said to have "wiped the eye" of the previous, unsuccessful handler. Wiping eyes was a braggin' rights accomplishment among British field trialers.

On his way home from that stock dog trial, Dave Elliot realized what an advantage his dogs would have in retriever field trials if he could control them at a distance the way those stock dog trainers controlled theirs. So he started experimenting with lining, stopping, and casting. His retrievers took to this training quite readily. And he thereby invented the blind retrieve.

Actually, it was more borrowed than invented, but Dave Elliot deserves full credit for having the imagination to see how stock dog handling could benefit retriever work. One wonders how many other retriever trainers watched stock dog trials back then but went home clueless.

Dave became an eye-wiping legend in British field trials. In the late 1920s, certain members of the American economic aristocracy began frequenting British estates to hunt upland birds the English way. Impressed by the work of retrievers there, they began importing them, mostly Labs, to this country for similar work on their own extensive estates. Not being pikers, they also imported British trainers.

In 1931, Jay Carlisle "wiped their eyes" by hiring and importing Dave Elliot to manage his Wingan Kennel and train his retrievers. Consequently, Dave Elliot was a major player in the design of our field trial format, in which the blind retrieve was to become an art form.

By introducing the blind retrieve to this country, Dave also did us hunters a great favor. Now long dead, may he be blissfully happy in a place where PILs (poor initial line), slipped whistles, and cast refusals never happen.

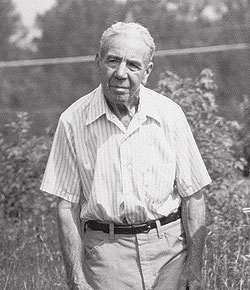

The elderly gentleman shown here is Dave El liot, the man who invented the blind retrieve in England back in the early 1920s. This picture was taken at an American field trial sometime in the latter part of Dave's life. Picture supplied by William Smith, Jr. |

When Is It Useful?

Obviously, anytime your retriever fails to mark a bird that you or one of your hunting buddies knocks down, you'll find being able to "handle" him to it a great advantage. This is especially true in waterfowling, where your only other options are wading or rowing.

Even when hunting wildfowl on land, having a dog trained to do blind retrieves will save you a lot of walking and keep you near the blind where you belong in case unexpected guests visit your blocks while Old Mallard Muncher is out picking up a long fall.

When hunting waterfowl on public land and lakes, you might get an occasional request for canine assistance from hunters in other blinds who either have no dogs or whose dogs don't do blind retrieves. You may find yourself putting on a bit of a show in these situations, and why not?

Of course, the blind retrieve can become quite handy in certain upland hunting situations, as well. For example, you might knock down two rooster pheasants, one of which falls about 20 yards in front of your pooch, while the other one drops unmarked on the far side of a deep creek. Or while your dog is retrieving a single quail you shot, another "sleeper" quail might flush unexpectedly, and fly over a small lake and fall there when you shoot it.

And so on.

Then you will sometimes have to handle your dog to a bird he has marked but cannot find. After he hunts the area of the fall unsuccessfully, he'll start hunting a wider and wider area and may disturb other birds if you don't step in and direct him to the bird you shot. When this happens, just toot the Sit-whistle, and cast him toward the bird as often as necessary.

Finally, having a retriever that does blind retrieves can make you the most sought after hunting buddy in your area. You'll get more invitations to hunt than you can accept, which is nice, because you can accept only the most promising ones. You'll not only get to hunt places you couldn't otherwise even visit, but you'll also get lots of free lunches, and now and then a free after-sundown glass of beer.

Nota Bene: Jim Spencer's books can be ordered from the Gun Dog Bookshelf: Training Retrievers for Marshes & Meadows; Retriever Training Tests; Retriever Training Drills for Marking; Retriever Training Drills for Blind Retrieves; Retriever Hunt Tests; HUP! Training Flushing Spaniels the American Way; and POINT! Training the All-Seasons Bird Dog.