Producing expensive ammo at cheap ammo prices is but one reason for rolling your own.

By Layne Simpson

We shotgunners have a number of reasons for stuffing empty hulls with shot and powder and one of them is saving money. The availability of cheap ammunition presently being imported from Russia and other places has narrowed the cost gap compared to what it once was but the difference is still enough to make reloading worthwhile.

The Dillon progressive reloader automatically feeds empty hulls from a blue hopper positioned above the powder and shot reservoirs. |

My cost on a box of 12-gauge reloads I use when shooting skeet is about a dollar less than what I would pay for a box of promotional ammo at "mart" prices but the difference does not stop there; the extremely hard, high-antimony shot in my ammunition almost always delivers better patterns than the soft shot used in economy-grade factory ammo.

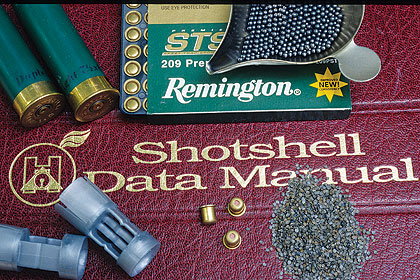

When the cost of top-quality factory ammo is compared to the cost of my reloads the difference becomes even greater. Even at discounted prices, high-end target loads such as Federal Gold Medal, Remington STS and Winchester AA are upwards of three times as expensive as my reloads and premium-grade field loads are even more so. The capability of producing expensive ammo at cheap ammo prices is but one reason for rolling your own.

Load Options

Reloading also offers the option of building loads that are not available from the factories. For example, a 12-gauge load with 7„8 ounce of shot is available off the shelf but not necessarily in the form we might want or need. That shot charge weight as well as the similar 24-gram load is available only in No. 71„2, 8 and 9 shot and anyone who needs another shot size and does not reload is out of luck. There is one other thing here.

Its ability to simultaneously perform all the necessary operations at its multiple stations enables an auto-progressive reloader to produce a loaded shotshell with each cycle of its operating handle. |

Factory loads with either of those shot charges are loaded to 1,325 feet per second (fps) and higher and that's faster than necessary for some of the applications for which a light shot charge is so well suited. On top of that, recoil is more than some shooters want in a lightweight gun.

Reloading allows me to back off on the throttle to around 1,150-fps with 7„8 ounce of shot and in doing so make a 12-gauge gun kick like a 28-gauge gun. It is excellent medicine for shooting skeet, for 16-yard trap, for some shots in sporting clays, for shooting quail over a pointing dog and for most of the dove shooting I do.

Light-recoil handloads are also just the ticket for older guns. My 51„2-pound Westley Richards double in 20-gauge was built during the 1930s and while its action is tight as a tick, I have no desire to pound it to pieces with heavy factory loads, some of which generate close to 12,000-psi chamber pressure. Ron Reiber of Hodgdon assisted me in the development of several loads for my gun that churn ups a bit less than 8,000-psi and yet they are quite deadly in the field. Recoil is also quite comfortable.

One that I really enjoy using is actually a 28-gauge equivalent load with 3„4 ounce of shot. Capacity of the shotcup of the Winchester WAA20 plastic wad used in that load is reduced by inserting a .125-inch, 32-gauge felt wad prior to dropping in the shot charge.

A single-stage reloader requires the operator to manually move a hull from station to station until it becomes a loaded shell. |

I covered spreader loads in more detail in another column so I'll keep it brief here by simply saying that cooking up recipes that serve to increase pattern size delivered by tight-choked guns is another advantage offered by reloading. A plastic insert shaped like a giant thumbtack is placed post-down atop the shot charge before the shell is crimped; patterns delivered from a barrel choked Full are as large in diameter as those fired by a barrel choked Improved Cylinder and Modified choke is opened up to Skeet or Cylinder Bore.

Called Poly-Wad, it is available from Magnum Performance Ballistics (800-998-0669). Sometime back I was invited on a bird hunt where we all had to use guns of American design introduced prior to 1900. The Winchester Model 1897 that I took on the hunt certainly qualified in vintage but its barrel is choked too tight for anything except pass-shooting ducks at great distances. The spreader loads I used transformed a tight-choked gun into one that threw Improved Cylinder patterns.

Then we have the sadly neglected 16-gauge. Those of us who hunt with 16-gauge guns have little choice but to handload simply because not many options are available.

Remington still offers three loads (one with steel shot), Federal has cut back to a couple of loads and Winchester is down to a single 31„4-dram load with 11„8 ounce of shot. A few smaller companies also offer several loadings but when compared to numerous loads available for the other gauges it is easy to see that not a lot of 16-gauge options are available from the factories.

Some that are available churn up too much recoil in light guns. I love to hunt with my father's old 16-gauge L.C. Smith but since it weighs only 63„4 pounds, it is uncomfortable to shoot with most of the available factory loads. The handload I use most in it pushes an ounce of shot along at 1,100-fps and in addition to being gentle on the shoulder, it has proven quite effective on birds ranging in size from bobwhite quail to ringneck pheasant.

I am also experimenting with 7„8- and 3„4-ounce loads for that gun, something I could not do if I did not reload. I could go on and on but you get the point by now--handloading enables the shotgunner to fill a lot of performance slots left open by factory ammunition.

There are three basic types of shotshell reloaders and all have a number of stations, each of which performs one or more steps of the loading cycle. When using an inexpensive single-stage machine such as the Lee Load-All and Mec 600 Jr., you start with a single hull and, as you operate the lever with one hand, your other hand inserts and removes the hull from each station until it becomes a load

ed shell. If the machine has five stations its handle will have to be cycled at least as many times in order to produce a loaded round.

Anyone who decides to start reloading shotshells should buy the Hodgdon data manual before buying a reloader. |

Add operations such as wad and primer insertion and operating the combination shot and powder charging bar and it can take well over a dozen movements of the hands in order to produce a single loaded shotshell.

Moving from the least expensive to the most expensive, the auto-progressive machine produces a loaded round with each cycle of its handle. It accomplishes this by simultaneously performing all operations with each of its stations containing cases in various stages of completion. Most progressives also automatically dispense primers, powder and shot; Dillon and Ponsness-Warren offer machines that feed empty hulls automatically as well.

The third type of reloader is the manual-progressive and unlike the auto-progressive, which automatically rotates the shell holder, its shell holder must be manually rotated after each cycle of the operating handle. The Mec 8567 Grabber is this type of machine and while it is not as expensive as the fully automatic loader it is considerably slower. Deciding which type of loader to buy boils down to how much shooting is done.

Assuming no stoppages, a single-stage machine is capable of turning out 100 to 125 loaded shells per hour. Those who reload mainly for hunting and perhaps a round or two of skeet or sporting clays each week can live happily ever after with this type of loader. I use the 16-gauge as well as the 3-inch .410 only for hunting so a couple of single-stage presses are fast enough to keep me supplied with both during a season. I load all my .410s on a Mec 600 Jr. and a Lee Load-All keeps me supplied with the few 16-gauge shells I use each year.

I hunt with the 28, 20 and 12 gauges but since I also shoot clay targets with them my demand for those gauges far exceeds my ability to produce an adequate supply on anything less than fully automatic progressive machines. More specifically, I load the 28 on a Ponsness-Warren 950 Elite, the 20 on a Dillon SL900 and the 12 on a RCBS Grand. With either machine I can easily turn out 400 to 450 top quality shells per hour.

Along with your new home shotshell factory you will need a powder scale to confirm that the powder bushing you have installed in the machine is throwing a charge of the correct weight. The Dillon reloader uses an automatic powder measure rather than bushings but a scale is still needed when adjusting the measure to dispense the desired charge weight.

Add a reloading manual or two containing load data published by the various propellant manufacturers and you are all set in the accessories department. Hodgdon and Lyman have the best shotshell manuals presently available and I highly recommend having both.