English Setters And American Bird Hunters Go Way Back

By Dave Carty

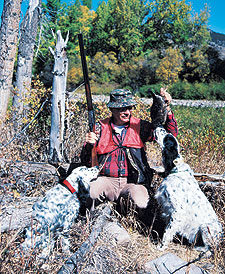

You'll find setters just about everywhere gamebirds are hunted in North America, including the rocky slopes that chukars inhabit. |

Here in the colonies, though, we like our field sports rough around the edges, and despite a well-heeled effort by some to lock up, lease, and sell wildlife that belongs to all of us — don't get me started--it falls to our dogs, especially our pointers and spaniels, to find birds for us. The fetching part is the icing on the cake, at least as far as most setter owners are concerned.

Truth is, it's been a while since setters have been known for their retrieving abilities, if ever. It's also been a long time since setters dominated our version of English gentility, i.e., the National Pointing Dog Championships in Grand Junction, Tennessee. The last — and only — time I was there, there were something like two or three setters entered in a field of approximately 40 pointers, although the pointer's connection to England is even more tenuous than the setter's. Go figure.

That most setters can't compete with a pointer's raw, physical stamina and range in a brutal three-hour horseback trial is not necessarily a bad thing. A lot of people can't compete with the raw, physical talent of Michael Jordan, either, but that doesn't mean that any one of us, given enough practice, couldn't get pretty damn good at a game of horse.

And so it goes for setters. Believe me, there's enough run and drive in a good setter to keep just about anyone happy, even a veteran, if aging, foot hunter like me, who happens to like hard-charging, big-running dogs. And as for style, well€¦watch a setter with a twelve o'clock tail stick a covey of Huns and then tell me just what it is on this green earth that is prettier than that. George Hickox once told me that his description of a good bird dog is a dog that runs and finds game in a way that pleases him. He got it exactly right.

My setters please me. All the setters I've owned or trained have been small, fast and flashy, although there's a sizeable contingent who like larger, slower dogs, among them the Ryman, Old Hemlock and DeCoverly strains. I've hunted over several of these jowly, galloping animals and most have been fine dogs indeed, with plenty of bird sense and drive. My impression is that, at the end of the day, neither style has a monopoly on game produced for the gun. To each his own.

Common to all setters — or at least, virtually every one I've been around — is a warm, loving personality. Brittanys are the imps of the dog world, as happy to tweak your proper sensibilities as they are to charge into a stand of muddy cattails after a running pheasant. Labs are big, happy-go-lucky goofs, always ready for a game of fetch, and pointers can be surprisingly clownish, although that's hardly their reputation.

Springers seem driven to work, possessed of inner demons that drive them to do something, even when they're not hunting. But setters, almost to the dog, will hunt their hearts out in the field, but when the day is done, seem content and happy to curl up in your lap, gaze languorously into you eyes, and then nod off into dreamland.

A setter in the autumn grouse woods is as much a part of the upland gunning tradition as a fine double-barrel. |

Their calm temperaments hardly reflect a lack of will. When I was training my setter, Scarlet, things progressed reasonably smoothly until we got to force fetching. She'd done everything else just right: the "whoa," "come," and "heel" commands, and had steadied up nicely to wing and shot. But force fetching, apparently, was beyond her notion of duty. The first time I shoved a canvas dummy in her mouth, she screwed up her pretty face, gave me a look dripping with disgust and spit it right back out in my hand.

No amount of ear pinching would change her attitude; there were some things she just wasn't going to do. It took me all of three months to get through to her. To this day, I've yet to force-break a dog who fought me as long or as diligently. To her credit, she's now a reliable retriever — not pretty or particularly enthusiastic -- but reliable.

Her drive is something else again. Certainly, Scarlet has faults; on some days she false points incessantly, and because she's deaf in one ear, she can be infuriatingly selective about hearing commands she's not interested in obeying. But inside that slender, 35-pound body is a fire for the hunt that simmers or roars depending upon the day, but never, ever stops burning.

Her drive is at times her Achilles heel. I began hunting blue grouse several years ago when I could no longer justify running my dogs in the torrid September heat that passes for opening week on the prairies. It's cool in the mountains — relative to the prairies, anyway — and besides getting an excellent workout, the dogs usually manage to put up a half dozen blues, one of the more interesting and certainly more underrated gamebirds around these parts.

On this particular day, I was hunting with two of my friends, which as it turned out was a stroke of luck. Despite the elevation, it was a scorcher down in the valley, and by 10:00 a.m. the heat had worked its way up the mountain. Still, Scarlet was hunting well, and whenever she swung by, I'd call her in for a drink of water. Sometimes she refused, anxious to get back to the job at hand. Then, suddenly, she was walking directly behind me.

I sent her on, but she seemed unwilling or unable to understand. I sent her on again, and although she tried to comply, she seemed to be losing her balance. Alarmed, I watched as she tried to negotiate her way around a small log she'd have easily leapt over just minutes before. Something was very wrong.

When I finally got down on my knees and gazed into her eyes, she was obviously disoriented. That scared me. I called my friends over, gave one of them my shotgun, and picked her up. The three of us took turns carrying her the mile and half back to the truck. By then she had begun to recover a bit and I'd had time to think about what had gone wrong.

English setters combine a high degree of field ability with an affectionate, companionable personality...it's no wonder they have long been one of our most popular sporting breed s. |

I figured she was hypoglycemic, and a subsequent exam by my vet confirmed my suspicions. Scarlet, it turned out, had simply run herself out of blood sugar. Undoubtedly, she knew long before I did that something was wrong, but she'd been too driven to find birds to quit.

After that, I learned how to modify her pre-hunt feedings in a way that usually solves the problem, but she still pulls up wobbly-legged and glassy-eyed on occasion, my signal that it's past time for her to quit, whether she wants to or not.

It's tempting when you write about dogs, especially your favorite breed, to declare that such and such a breed is the "best." With the exception of a couple of breeds I'm pretty certain will never earn that designation (and I'll never reveal for fear of death threats from fanatic aficionados), all breeds produce good lines of dogs, and within those lines are any number of really outstanding individuals, dogs that always seem to have their ducks in a row. But raw talent doesn't always mean more birds produced for the gun.

My two setters, for instance, outrun most of the other breeds I've hunted them with, and they've got birdiness up the yin yang. But does that mean they always find more birds? Nope. Scarlet and Hanna have been outgunned by pointers, German shorthairs, a Lab or two, springer spaniels, and quite often, by my own not-particularly-humble Brittany. That I'm still a hardcore setter fan says as much about my personal esthetics and sense of the way things are supposed to work as it does any squinty-eyed accounting of the pluses and debits of the breed itself.

Some of that romance must go back to my midwestern childhood. I didn't have a setter then, but I did have an allowance, which bought an occasional copy of Field & Stream; and the pages of Corey Ford's "Lower Forty," my favorite column, were salted with references to English setters and New England grouse coverts. I grew up convinced that English setters, abandoned orchards fenced by crumbling rock walls and side-by-side shotguns were how all real outdoorsman were supposed to hunt, and planned on becoming a real outdoorsman myself as soon as I grew up.

Despite predictions to the contrary, I actually did grow up, but I hightailed it west first chance I got, and finally bought a setter in my early thirties. We don't have abandoned apple orchards in Montana, and I've never seen a rock wall out here, abandoned or otherwise (although we have plenty of rocks). But we've got oceans of wheatfields and ten thousand square miles of prairie. Setters, I quickly learned, were just as good in the wide open west as they were in the woods of New Hampshire. English setters, indeed. Setters are as American as Model 12s and Maine hunting shoes.

The flowing beauty that setters are justly famous for comes with a stiff price, however. Supposedly, the breed's long, silky hair protects them from burrs and briars, but you can't prove it by me. After years of wrestling matches on the back of my tailgate where my dogs screamed in pain as I yanked burrs out of their hair and I screamed in frustration, I finally threw in the towel and decided to give every last one of them a buzz cut. This usually takes place just before the season opens and again late in the year, before (or if I'm lazy and forget, after) I head south to hunt desert quail, where a particularly low-life form of burr the locals call bugles thrive with equatorial fecundity.

The wide-open spaces out west provide plenty of opportunities for setters to demonstrate their inborn talents. |

There's still enough hair on my dogs to keep them comfortable through Montana's typically bracing Decembers, but as hard as they run, I could probably shave them down to bare skin and they'd still stay warm. You can leave the feathering on the tail if you're hung up on the whole Edmund Osthaus thing.

Surprisingly, my dogs' feet seem to hold up reasonably well in the rocky southwest, but chukar hunting is a different matter. Chukars live on almost pure rock, with just enough dirt and cheat grass between to hold the chunks together. Even tough-footed dogs can't run for long in chukar country without foot problems. Conditioning your dog's feet with long runs and a pad toughener will help, but if you and your setters are planning a multi-day expedition to someplace that's rocky, buying a couple sets of dog boots (guaranteed, you'll lose at least one or two individual boots over the course of a week) may be the expense you didn't really want to make that saves the trip.

Finally, take your setter hunting. Every day if you can swing it. She may be perfectly happy sleeping at the foot of your bed€¦but she'll really come alive if you hunt her.