A dismal week brightens with the reward only a grouse hunter finds.

By Peter W. Fong

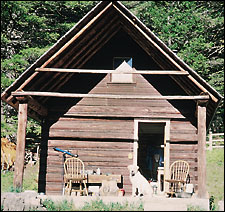

We arrived at the cabin in late afternoon, just as the shadow of Grouse Ridge fell over the porch, with a five-year-old boy, a one-year-old girl, a big yellow dog, and a flat tire. It had been a four-hour drive, in two separate vehicles, and my wife and I were both subdued and mildly amazed. After a dinner of cold chicken, we walked back to the west to catch the last warmth of the fleeting sun, threading our way through range cattle of various colors and temperaments: black, tolerant, whitefaced, skittish, shorthorned, indignant. From the ridge, we could see miles of country and acres of possibilities--the alpine meadows near Hogback Lookout, still bright with Indian paintbrush and brown-eyed susans, the great gray spires that guard the Beaver Creek Canyon like stone sentinels, and far below, the dammed and humbled Missouri.

I'd been dreaming about this trip to the Big Belt Mountains for months, thumbing it like a trump card in an otherwise unremarkable hand until it fairly gleamed with purpose and prosperity. In our lives, September marked the beginning of everything: fiscal-year budgets, health-plan deductibles, kindergarten, hunting. The old year--with its long indoor summer of deadlines and contracts--was a closed book. The new year, resurrected by the opening day of grouse season, was only two sunsets away.

The next morning, I tightened the lug nuts on the spare tire, tucked the flat behind the front seat of the station wagon and headed back to the nearest town, alone. Halfway to Helena, I heard on the radio that Elvis had died--20 years ago that day, but still news, and thousands had gathered at Graceland to remember him. In his 42 years, the King had produced 18 number-one singles, 33 movies, and countless unauthorized biographies. He had sweated and toiled until, finally, his heart had given out like a used carburetor.

With the spare on the driver's-side front wheel, I had to lean hard toward the center line to stay on the road. While leaning, it occurred to me that, in the year of his expiration, Elvis had not been much older than I was now, and yet here I felt hardly used at all. I vowed to work harder towards that end, and resolved that I would not forget the King's dying day again either, that his passing would, for now on, be inextricably linked with the smell of road dust, the crack of gravel under bald tires, and the heft of a lug wrench in my hand.

I made it back to the cabin by midday, feeling somewhat overheated by the sun and throttled by thirst. We loaded the kids into the car and drove down to Trout Creek with swimsuits and towels only to find a bed of dry gravel. We hiked into the canyon anyway and were rewarded with more views of towering rock spires, carpets of bunchberry dogwood with their cardinal red fruit, and the occasional ripe raspberry. While the dog worked the edge of each thicket, I tried not to imagine the grouse flushing, the slap of the stock against my cheek, the report of the twelve gauge.

Instead, I prattled inanities for my daughter's amusement, tickling her bare feet as she rode in the baby pack, and reaching over one shoulder with the sweetest berries cradled like gems in my open palm. We met a German couple on the trail hiking with a white Pomeranian, a black Rottweiler, and no water. The air was parched even in the shade of the canyon and the big Rottweiler's tongue looked as dry as a razor strap. The Germans had been traveling around North America for five years: Canada and the United States in the summer, Mexico in the winter. They gave no explanation for their restlessness, and none was needed. At the end of the conversation, they admitted that they really had nothing to complain about.

Later in the afternoon, we motored back up to Indian Flats and down the western set of switchbacks to Beaver Creek for a real swim. Then we lit a fire and sliced mushrooms and red peppers into a cast-iron pan. While the kids gorged themselves on marshmallows, my wife and I roasted some cubes of last season's elk, warmed two slices of sourdough bread, then cracked a bottle of champagne. We really had nothing to complain about either.

The grouse season opened the next morning: ruffed, spruce, and blue. Ordinarily I would have been up before dawn, walking the ridge across from the cabin, the dog running ahead of me with his tail up and his nose down, flushing birds far out of shotgun range. But this day I sat quietly on the porch, keeping watch over two sleeping children while my wife tried to accumulate an hour or two of peace and quiet, like a bear hoarding the memory of huckleberries against winter. She'd have both kids during the week, while I stayed at the cabin with only the grouse and the dog, so I didn't feel too badly about the half-dozen shotgun blasts that found my ears from the other side of the ridge. I still counted them, of course, but I did not count each one as a dead bird and reckon the decline in the remaining population. I wished those other hunters the best of luck on the last day of the Labor Day weekend, because tomorrow morning they would be at work, while I--still younger than Elvis--could hunt as I pleased.

Home at last. Boy and dog seem totally unaware that in just two days, the grouse season opens. |

But after I'd walked Grouse Ridge myself, with the setting sun at my back, and then again with a rising sun throwing shadows ahead, I had to wonder what yesterday's hunters found to point their guns at. I saw gray jays and mountain chickadees, red squirrels and red-breasted nuthatches, gnarled old fir trees with big branches for roosts, rocky knobs overlooking thick clumps of spruce and open meadows alive with grasshoppers. But no grouse.

That second afternoon--which seemed to promise many more hours than any one day could hold, long quiet hours with no demands other than my own--I decided to drive back down Beaver Creek to its confluence with the Missouri, to hunt the cottonwoods in the creek bottom and the sagebrush hills that rose like sleeping elephants from the meadow grass.

If the kids had joined the Lab and me, we might have taken a trip to the Eldorado Bar to mine sapphires, which is in its own way as much fun as hunting Easter eggs or morel mushrooms, and requires the same sort of optimism and concentration. Or we might have dunked worms in a deep eddy of the river, prospecting for carp or walleye or who knows what, since any live thing on the end of a fishing pole is enough to make them smile.

But the kids were gone until Friday. My son would learn to color and to cooperate and to cope with all the petty boredoms of kindergarten. My daughter would test her ability to stand after twirling 20 times on the carpet, shake her

head "yes" for no and "no" for yes, reward her mother's attentions with unreasonable screams and unexpected smiles.

Thinking of them, I felt again that vague sort of inadequacy inspired by the death of the King. A shameful feeling, as if I had been caught whining or shirking or coveting my neighbor's goods. I reminded myself that my family had returned home in the car. I remained here with the truck. These were my days.

The Labrador and I bumped along beside Beaver Creek to within a mile of the Missouri, then turned north onto a spur road towards the Gates of the Mountains, through an old burn with bare hillsides, thinly populated by weathered and broken stumps. The route was generally dusty, raked by a dry wind that reeked of barren rock and burnt sage, so I was altogether unprepared for what lay at the end: red-and-white signs announcing private property, a cluster of trophy log and cedar homes with monstrous picture windows, a neat row of boat docks, and the cool green river.

We sat in the truck with my forearm propped on the window ledge, gawking in not quite the same way as Lewis and Clark must have from the same vantage point. Feeling that we were being watched, I looked up to find a middle-aged man like myself in a white t-shirt leaning on the railing of a bright, unweathered deck. I waved, but he did not wave back.

On the way out, I noticed a tiny marker for Spring Gulch that I'd missed on the way in. I parked and looked up the ravine, noticing first a trail of tansy and golden asters, then the green ribbon of grass, and finally the thick clumps of snowberry and wild roses. I grabbed the shotgun and a handful of shells and started up after the dog, following a trickle of live water past thickets of chokecherry until the gulch narrowed and fir and pine began to close in. On the way back down I sent him into every likely looking hole but no grouse flew out.

|

Perspiration was pouring off my face by then and my feet were sweat-soaked inside their boots. But for some reason known only to unlucky hunters, I could not leave this place without firing a shot. It worked beautifully now, mounted on the rinkydink spare tire that my father and his wife had left in our garage before their last trip to Alaska, and I shot my way through a box of shells, hitting something less than 50 percent, so much less, in fact, that when I broke just one of the last round of three, I decided to give up and declare victory. My Lab just whined. We hadn't seen birds in as fine a piece of grouse habitat as there could possibly exist, but at least I had warmed up the barrel.

When I reached Beaver Creek again, another hunter was already working the line of cottonwoods I'd picked out for myself. So I sat on the tailgate munching on elk sausage until a squall blew down the canyon, bringing rain.

We hunted up Hogback the next morning, surrounded by clouds. I wanted to gain enough elevation to find blue grouse--the big noisy birds that I had often seen while elk hunting but never with a shotgun in hand. For the first dim hours after dawn, with an importunate and tangible mist limiting visibility to ten paces, I was not exactly hunting. But I was hiking, and carrying the gun, and it was no small pleasure to experience that dizzy and unanchored feeling of walking in clouds.

By mid-morning, when the dog and I turned back for the truck, the clouds had burned off, and we could see where we'd been and the limitless miles of country around us. The clouds had left droplets of moisture on every pebble and pine needle, glimmering in the light like newly faceted jewels. As we walked along the sharp edge of the ridge, the dog found a blue grouse hiding in a juniper and charged. We both watched it explode from the ground and sail off into a thousand clean feet of air, wings spread like a bird of prey, gliding over the canyon until it was no more than a dim speck of gray feathers. Neither of us offered to follow.

Although I hadn't so much as lifted the gun to my shoulder, the sight of the grouse was like a balm to my heart. Not that I had felt sick exactly--in my third day of fruitless hunting--but still there was comfort in the mere presence of grouse, a signal of renewed hope, like the swoop of a frigate bird over blue water, or the smooth curve of a fresh elk track.

An hour later, near the base of the ridge, another blue offered me three shots. The first, low and quartering away, missed behind; the second, as the bird was rising, disturbed enough air to encourage him to wheel back above me; the third, awkwardly overhead, was a futile prayer.

The dog gave me the long-suffering look that he'd practiced during last December's waterfowl hunting, and perfected on the final morning of that season, when the ducks flew like there was no tomorrow and I responded like a five-year-old with a fly-swatter, flailing wildly at the whistle of wings. On that day the skies had settled by noon and we spent the hours until dusk in a frantic search for redemption.

I took some consolation in actually seeing a grouse that could be shot at, but what I remember of course is the bird overhead, tail feathers fanned outward like the night's best poker hand, wings spread like a net to catch the blue sky.

At lunch time, I sat in the sun on the front porch of the cabin, eating cold potato soup, and sipping bourbon from a Mason jar. The afternoon brought wind and rain again, and then only rain. Nonetheless, I picked up the gun and walked out to blunder among the grouse. Shuffling along below the crest of the ridge, I tried to pretend that it was duck season again, that I had forgotten my raincoat instead of merely overlooking it, and that I could hardly allow such a trifle to douse my enthusiasm.

The gray light threw what color remained into stark relief. Red-orange of Indian paintbrush, purple asters, the pearl white of yarrow, blue of harebells, and the occasional yellow of a brown-eyed susan. The grouse were feeding warily, very near the timber line, in a scrubby patchwork of juniper and bearberry. I flushed four birds, or perhaps two birds twice each. I took one shot as a big blue flew low through into the timber, but dropped only a fir branch. Walking back to the truck, head down against the wind and soaked to the skin, I spotted a fossilized seashell imbedded in a fist-sized chunk of wet black shale--a remnant of the ocean floor 7000 feet above sea level, a reminder that even the lowliest of the low may someday rise.

The next day's grouse came, of course, when I least expected it. I'd been watching a long-legged hare, still in his summer coat, trace a series of zigs and zags up a rocky terrace, loping along in a graceful and considered fashion, as if he were entirely aware of the yellow dog 50 yards behind him, and even more entirely aware that said dog would not think to look up and apprehend him while said dog's nose was glued to the twisting trail of scent.

Small accommodations, but a spectacular view under Grouse Ridge. |

I shifted my weight to the uphill foot, in preparation for taking a step toward the hare, when the big blue rocketed out of a juniper 20 yards off and flew at an angle that brought him within fifteen yards, moving left to right, his big wings pumping like a wild turkey's.

I brought the gun up and touched the trigger before the muzzle had cleared even his tail feathers. The grouse turned his wings under the wind and veered off downhill. Humbled and despairing, I wasted another shot at his back. The dog looked up momentarily from the rabbit trail to see what all the noise was about, heard me swear softly, watched me stoop to collect the spent shells, then went back to his work.

The grouse hung in my mind like a pinata at a child's birthday party, in which I was the blindfolded guest who swung and missed and swung again and missed again.

As I worked back up the slope, I thought of the theory of success I'd developed as both a guide and a commercial fisherman--go far enough, work hard enough, and it will come. The "it" being that moment when fish and fisherman find themselves wired together, jolted by the same not entirely unexpected current, almost as if each had predicted the other's capture. This theory seemed to apply with equal relevance to mountain streams and the gulfstream, to palm-sized trout and man-sized tarpon. I desperately wanted it to apply to upland birds as well. Melded to the old urge to chase was the more enduring urge to provide, at least in some symbolic fashion, if not in the real terms of meat and bone. I did not want to explain to my children how I could hunt every day for a week and not taste even one sinewy drumstick.

I watched a family of ravens playing in the updrafts created when the wind slammed into the side of the mountain, their black wings spiraling high into the blue, doing loops and barrel rolls, cawing to each other as if to ask, "Can you top this?" Then I turned my back to them and ran to catch up with the dog.

Although each life we take for our own sustenance is a gift, this bird was more like a king's ransom. I had given up for the evening, hiking head down again for the truck, when I saw the grouse running ahead of the dog in a little alley of open ground. It lifted off from the uphill side of the opening, turned and followed the steep contour of the mountain, bringing it back below me. My first shot went high, as did the second. I watched as pellets scattered bits of bark from the trees downhill and behind the bird. This blessed grouse could have easily escaped into the thick timber, but instead it kept on as straight as a homing pigeon. By some miracle the third shot found feathers, and the bird dropped like a wicker basket. It hit the rocky slope about 50 feet downhill, then rolled another 20. The dog scrambled down and picked it up in his mouth. When its wings flapped uselessly, he let it fall. I asked him to bring the bird a half-dozen times to no avail, then finally started down after him. Seeing this, he picked it up again and carried it to me.

I can't explain this behavior from a dog who has swum with a wounded goose across an ice-choked river, receiving a staccato beating about the head and ears all the while, then delivered the exhausted bird perfectly to hand, except perhaps as an expression of a dog's disgust at my shooting in the past week, his way of saying, "You don't deserve this beautiful grouse and I am withholding it for your own good."

Back at the cabin, I admired again the plump heft of the bird, so much weightier than the ruffed grouse that frequent the woods near our home. I dressed and plucked it while it was still warm, saving the black tail quills for my son. I stowed the cleaned carcass in the cooler for dinner the next day, with my returning family, then sauteed the heart and liver in garlic and butter, served it with a plateful of egg noodles alfredo and a handful of steamed green beans, picked from our garden on the morning we left home, and still so crisp that they squeaked between my teeth.

The heart was tasty but the liver was like a healing tonic, smooth and succulent, with the almost medicinal tang of juniper that you find in straight gin.

Peter W. Fong is the author of the award-winning novel, Principles of Navigation, and the head guide at Mongolia River Outfitters. He lives in Tangier, Morocco.