From the Carolinas to the Golden Gate, big fields offer the same prizes...and the same problems.

By Charles F. Waterman

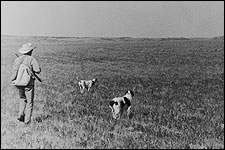

Big fields require no special breed of pointing dog but they bring out new sides to dog personalities. |

It was five miles around but it wasn't the biggest of the fields. I checked it with a truck after I had walked it a few times. It is quite a patch of wheat stubble but there are other fields that could use it for a centerpiece.

I want to impress upon you that I am not discussing any garden plots or window boxes. I am referring to ground where a long-legged pointer can burn his candle at both ends and stumble over nothing but stubble and his own feet. There are big fields here and there from the Carolinas to the Golden Gate with the same prizes and problems and the rules are similar, but it is fun to deal with the big benchland operations of the West because that's where I've used binoculars on my own dogs more than anywhere else. Even a fireplace loafer is likely to take a deep breath and start reaching when you set him down with thousands of acres to scan.

I've chased several species through big fields, generally in stubble of one kind or another, although the term "stubble" might not quite apply to wheatgrass that has been cropped only by cattle after being sowed in rows and mixed with alfalfa. I've even collected ruffed grouse that had worked into wheat stubble from nearby willows and sometimes sage grouse operate in rye or wheat stubble. Sage grouse aren't grain eaters but they hunt for some of the green plants that are growing on their own.

Chukars slip out of the cliffs and boulders after the combines are through, sharptail grouse dote on such places and the Hungarian partridge is a big-field regular, looking for both grain and greens. Bobwhite quail aren't noted for open country but won't turn down scattered grain, and pheasants are sometimes out there in the open, likely to cause nervous breakdowns in any but the most philosophical pointing dog. I guess nearly all of our upland birds get into the wide-open spaces now and then--along with all those ducks and geese.

Big fields require no special breed of pointing dog but they bring out new sides to dog personalities, and handlers find some brand new puzzles in behavior. A view of shoe-polishing old Spot a quarter mile away and going strong is disconcerting and a rigid point at that distance may come as a crisis. And almost any game bird can run pretty fast between rows.

There are big-field dogs, not always the biggest goers but dogs that simply like it out there. I knew one old fellow who wasn't even a very staunch pointer anywhere else but would stalk and hold a covey of stubblefield Huns as long as it took. It's been a long time but I can still see him (some kind of a cross with a setter and a spaniel), a dark speck in the middle of a 160-acre wheat field with his birds well out ahead of him and staying put. We could see him because we were trying to keep track of him from the side of a rocky ridge. We'd figure on quite a hike when he was in top form. Now that's not the way most big-field birds should be handled. Generally, they don't even require an exceptionally wide-ranging dog, but in this case the Huns would fly down into the field from nearby ridges and often land near the middle.

That's unusual, and most of the big-field birds I've hunted were not too far from the edges, having walked in from heavier cover where they spent most of their time. In the biggest fields I've hunted, 90 percent of the birds were found within 300 yards of the edges. Control a dog well enough to keep him in that area and you should be in business. Study a particular situation and you might be surprised at how many birds you have. They establish a pattern of feeding, resting and roosting, and sometimes they cling to it slavishly. Your dog may learn it as well as you do and instead of a scatter you may have a concentration.

Dogs running in high stubble sometimes need underside protection. |

A few years ago, I had some of the most consistent Hun hunting I've ever seen--not easy but consistent. I didn't kill many birds but I sure saw a lot of them--or rather, I probably saw the same ones a lot of times. For years I had been hunting an enormous field of wheatgrass where Huns, sharptails and sage grouse would come out of some deep draws to feed each morning and evening.

The draws speared up into the field and birds could loaf in sagebrush and weeds between comfortable forays into the open. In years when the wheatgrass was heavy they'd scatter widely, but there was a drought that year, the grass was short, and they stuck pretty close to the little canyons. The dogs caught on and learned to work the edges just above the dropoffs. The birds were after greens with a few incidental seeds.

There was one stretch about 300 yards long where soil quality made the grass a little higher, and that's where birds congregated, and there was a prevailing wind that paralleled the long edge. Put the dogs down in the right place and they'd make game within five minutes, even if you did have to follow running Huns for 200 yards before they'd take off--usually out of range. But now and then you'd get close enough to shoot, often enough to keep me coming back for more. It was the most surefire 20-minute hunt I've ever known because I could park the truck at the downwind end of the productive strip. It was all Huns after the drought. The sharptails and sage grouse didn't show up.

Figuring out those Huns was no stroke of genius because I had been hunting them there for years, but there are a thousand somewhat similar setups that will work on birds from bobwhites to ringnecks and it sure wasn't complicated. A friend and I had a similar program on a big field that was put in wheat or rye for years and, like the wheatgrass, was set on a bench with heavy cover all around it. We didn't have any 200-yard sure thing, but a half-mile walk would almost invariably put us in business and several dogs learned that drill. We could drive a truck clear around that stubble, and although we didn't road-hunt we would drive to what we thought would be the right neighborhood each evening.

To show how addicted birds can become to a particular stubble stretch, we watched a single sharptail that walked back into the same 30-yard area three times the same evening after being driven off. Sharptail season was closed so we had sense enough to observe and never even put down a dog.

Sharptails are a strange mixture of steady and erratic performance. One little bunch stayed on the fringe of a wheat field for a month last fall and I had more than a dozen points on them

over that period. After I shot a limit of three birds they moved--200 yards. Since I found them in the cover instead of the stubble, they didn't run much. Because of dry weather the stubble was very short and there wasn't much chance of getting at them in late afternoon or early morning.

Big fields of stubble are generally a morning and evening proposition, but there is no hard and fast rule. Let's say birds are almost always there early and late and sometimes they're out there all day. Grass pasture or hay can be used for roosting and loafing as well as feeding if it's tall enough--and not too tall. Most birds need enough room to walk in, and some species insist on seeing out. That big wheatgrass field I was reporting on had such heavy vegetation several years ago that there were roosts all over it and those Huns and sharptails evidently didn't go into the nearby brush very often. The water business is hard for me to figure. They can get by with dew and snow, of course, but in hot, dry weather I think they generally find creeks or ponds.

After a long, cautious stalk, jumpy dogs come apart as Huns finally flush in the open. |

A good dog for fields that have held row crops needs some special skills you can't teach him--but he'll probably work them out for himself. He learns when the birds are running or holding, and he has a built-in sense of how close he can get when they move. Such an operator will follow birds with you beside him or slightly ahead of him, and sometimes goes as fast as you can walk, stopping and starting. I had one who actually rubbed my leg almost constantly when the moving started, a safety precaution that, nevertheless, made me jumpier than the birds. When the birds stop or you catch up with them, the real hotshot will take a rigid point and hold it, and I have seen a couple that never seemed to break upwind birds, the game always flying from the gunner instead.

The higher the cover, the more likely birds are to hold and when a combine has been set high in a good crop year you may get right on top of them, even a pheasant sometimes holding pretty well. Birds like to run between rows, of course, and if they get headed downwind things are complicated. Hunting upwind has a particularly big advantage in such sprinting areas. Dependent on your dog's size and the height of stubble, you might need something to protect his underside, homemade or commercial, for the clipped stalks can be pretty abrasive.

In considerable wind, with a dog holding tight, you may have a better chance at shooting if you circle out a little. On one frustrating evening last fall I had watched two big bunches of Huns flush wild after the dogs and I had hurried myself into near collapse following them. I'd about given up and was thinking of a hot shower and solitary meditation when two dogs froze solid and I approached from the side and well in front of them. Evidently the birds hadn't seen me at all and I stepped right into them that time--but random circling doesn't necessarily get you a shot and I think it's safer to stick with the nose.

There's an exception when you manage to get the dog downwind of you and with the birds between it and you, but planning that becomes major strategy and you need a tolerant sniffer who resists the natural impulse to work upwind from the gun. From near the edge, most flushes end up off the field so it's likely to be a single chance.

There's a completely different approach if you gauge your time right. You keep the dogs out of the field and let them trail game into it. This reduces the ground to be covered and has worked wonders with chukars that walked up out of a Washington canyon each evening. I caught them on a wheat field edge and they'd fly back over me after I joined the dog, but I first had to learn almost exactly what time of day they moved.

That's pretty much all I know about big fields.